—

Back in September 2022, I posted a piece on The Dylantantes called My Fraught Visit to the Bob Dylan Center. It tells the tale of my friend and I traveling to the Center for the first time and our experience with activists in the Greenwood section of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Greenwood was the neighborhood famously known as Black Wall Street at the turn of the twentieth century, and it was also the site of the horrors of the Tulsa Race Massacre in May and June of 1921, almost exactly 103 years ago as of this writing.

My piece was an attempt to summarize the Race Massacre, which many still have never heard of, and to grapple with the placement of the Bob Dylan Center Archive in the neighboring Tulsa Arts District, itself a site of considerable racial tension.

I am revisiting the piece because of recent news that a decades-old attempt by survivors of the Massacre to obtain reparations has finally failed in the Oklahoma Supreme Court. As unlikely as it sounds, two women who were child victims of the riot are still with us: Lessie Benningfield Randle (109) and Viola Fletcher (110). With this state court decision, any hope for even a sliver of justice for these women or the Black residents of Tulsa expires forever, just like the long-ago casualties of the racist rampage.

I wish I were revisiting this piece for the opposite reason — that these survivors have prevailed — but even that stunted degree of justice is simply not the way of Oklahoma apparently. Even if you agree with the ruling—perhaps, to be generous, on strictly legal grounds — it becomes impossible to ignore the persistent injustice still visited upon these innocent people. Indeed, it becomes impossible to deny that the cruelty is the point — a feature, not a bug, to lean on a cliche. Oh, and the racism. The cruelty and the racism.

The Tulsa Race Massacre is the century-old crime that just keeps on giving, it seems.

I hope you read or listen to this piece to the end even if you encountered it before. As Dylan fans we have a special responsibility, I believe, to understand a little better the context of the placement of the Bob Dylan Center and the horrific history of that place.

This revisited version is lightly edited from the original and is accompanied by an audio recording of the piece if you prefer. You can find the audio on FMPods.

As always, I hope to hear from you.

My Fraught Visit to the Bob Dylan Center Revisited

An Experience of Erasure, Dissonance, and the Consequences of Collection to Collective Memory

Well the future for me is already a thing of the past

Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

I have really made a commitment to myself to no longer be a victim of symbolic gestures of the killing, the oppression and just the horrible treatment of my ancestors.

The word of the day is fraught, as in “The city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, is racially fraught.” Fraught is somewhat of a weasel word, though. In its report entitled Our Generational Vision for Justice and Liberty, the Terence Crutcher Foundation states the case more plainly, “Tulsa is a city of state violence and unhealed hurts.”

The co-word of the day is collect and all its derivatives and adjacent terms: collection, collective, recollect, and so on. This essay is about the necessity of collection and the work of collectors to document our fraught history and present. After my trips to Tulsa, I am convinced that it is the collectors, archivists, and curators of past and present realities who offer any chance of saving us from our own worst future.

Bob Dylan Collects Scraps

Bob Dylan’s lyrics and commentary portray or reference periods of history almost compulsively. Be it the culture of the American Civil War, the music of the early twentieth century, the events and wisdom of Ancient Rome, or the circumstances and spirit of the Civil Rights Era, Dylan returns again and again to the past. Some call him nostalgic, and there’s a degree of that indulgence in his depictions, but only a degree. His portrayals of the past are most often aesthetically precise, idiosyncratically detailed, and politically savvy. Dylan puts his spin on history, to be sure, but he also seeks to preserve it with a degree of accuracy because the thread of truth is so easy to lose.

Dylan, of course, is not much interested in factual recreations — this happened, then that, then this other thing — although he is not above doing so. His depictions instead strive to get at an aesthetic truth. We can see this distinction play out in his unreliable memoirs, Chronicles, Volume 1, which is significantly if not mostly fictionalized even as the book purports to relate the mood and thinking of Dylan at particular moments in his life. Dylan is neither a historian nor a journalist, so his truth tends to be more curatorial than comprehensively collective. He’s an artist, and he does look back, sort of.

Think about his metal sculptures — scraps of discarded tools and machinery expertly combined to fashion a new reality. Dylan compiles the past to create pastiches throughout his art — painting, sculpture, performance, prose, poetry, and, of course, song. His relentless collecting of scraps helps recollect what came before in order to tweak our collective memory and forge a new understanding of the past and therefore the present and therefore the future.

Who We Are

If you watch the Netflix documentary Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, and I recommend you do, Civil Rights activist and host Jeffery Robinson quotes George Orwell’s famous truth from 1984:

Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

Robinson clarifies: “A government in power has the ability to shape the views of the population it governs by putting out a narrative that sometimes has nothing to do with the truth.” With his film, Robinson seeks to correct that narrative by collecting moments of our history and culture to create a coherent tale of American oppression. In many ways, Dylan’s contribution to the project of forging our collective consciousness is by thwarting any reshaping of the factual truth by preserving an aesthetic truth . After all, one can always dispute the facts, but it is difficult to argue with art.

Note, by the way, that the title of the documentary is Who We Are, not “Who They Are” or “Who We, the Members of the African-American Community, Are.” The “we” is sly and encompassing. It invites us all to contemplate our participation in the collective memory indicated by the subtitle: A Chronicle of Racism in America.

A Circular Journey through America

In late July and early August of 2022, my friend Geoff and I journeyed from his home near Philadelphia to Tulsa and the new Bob Dylan Center. We stopped in Pittsburgh for some baseball and then in Cincinnati to see some more baseball, this time with Graley Herren, whom I interviewed in an Ohio hotel where the room’s poor acoustics were easily overmatched by Graley’s incandescent commentary.

Geoff and I then spent several days in Tulsa before heading to Clarksdale, Mississippi, to visit some of the sites that originated the early blues masters — an arduous road trip for anyone let alone two middle-aged buddies crammed into a rented Chevy.

For the record, the Bob Dylan Center (BDC) is a gem and worth the visit as is the Woody Guthrie Center next door. Geoff’s a much more casual Dylan fan than I am and reports thoroughly enjoying the experience. The stated goal of the BDC curators had been to satisfy and delight the sometime fan as much as the true fanatic, so mission accomplished!

As collectors themselves, the curators of the Dylan Center and Archives tell a story of Dylan, his work, and our times through artifacts and art. As with any good study of Dylan’s work, once you have been to the BDC, you share in that collective memory. The BDC is a bald attempt to assure Dylan’s place in history before time — the impartial cosmic eraser — can get to him. Of course, sometimes or too often, history is also purposely erased.

Who We Erase

You have perhaps heard of the Tulsa Riot or Race Riot or Race Massacre, which took place over two spring days 103 years ago in the Greenwood District of Tulsa. Greenwood was the famous “Black Wall Street,” a national center of Black wealth and prosperity in this boom town seething with black gold and white resentment at the turn of the twentieth century.

Occupying recognized Indian Territory, Tulsa, I suppose, doomed itself from its inception as a nexus of racial violence. As if fated, the act of mass terror that took place in 1921 was much more than a massacre. Estimates of deaths range from dozens to hundreds to thousands. At least 10,000 Blacks were left homeless and destitute as their thriving community was burned to the ground, erased. Airplanes dropped firebombs from above as white terrorists on the streets ambushed and gunned down residents fleeing their burning homes. Afterward, thousands were interned for days—women and children in encampments outside the city and men in what until recently was known as the Brady Theater. Most fled. Others stayed but remained silent for decades for fear of reprisal. Their necessary silence of self-preservation combined with the white terrorists and their progeny’s self-serving conspiratorial silence are why you perhaps know little or nothing of the events of a century ago or learned of it only in recent years as I did. Through fear and collusion, history, like Greenwood, was consciously and purposefully erased.

All this was allegedly perpetrated because a group of armed Black men, war veterans, dared to stand in front of the jail to prevent a white mob from lynching a Black teenager. But really it was because a Black community dared to thrive and prosper, flagrantly flaunting their human dignity in the face of white gangsters and other city leaders.

You are likely familiar with the movie and its predecessor book Killers of the Flower Moon. The systematic mass murder of Osage people documented there took place near Tulsa and at virtually the same time as the Tulsa Race Massacre. These horrors, like the Trail of Tears, an ethnic cleansing that itself terminated in Oklahoma, and countless other abominations, were certainly not America’s first foray into genocide and racial displacement, nor would they be our last.

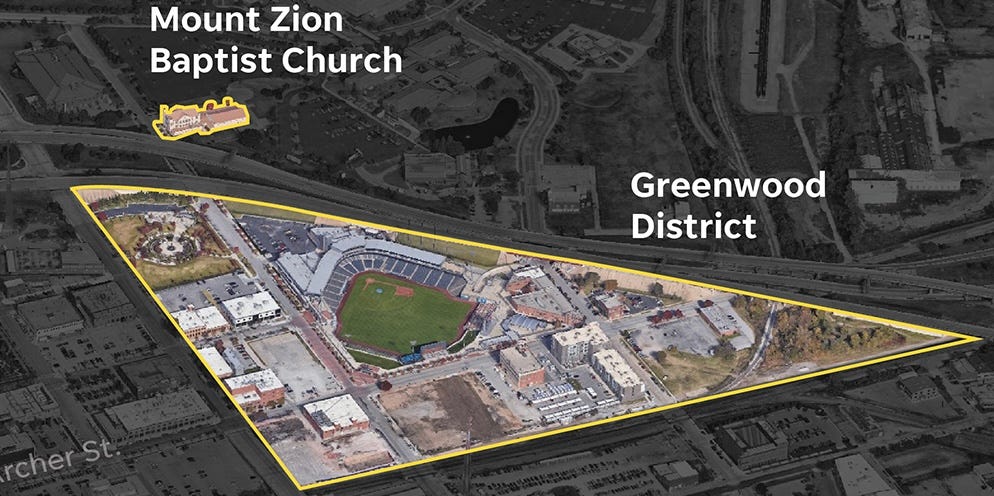

Which brings us to present-day Tulsa and its Greenwood District. All that is intact from Black Wall Street is an unassuming block of S. Greenwood Avenue, both sides of which are lined with renovated brick storefronts just north of E. Archer Street. The block terminates where Interstate 244 passes overhead. Anyone who knows anything about urban renewal and highway placement in the U.S. will recognize a common configuration, one that continues to be executed even today: a black neighborhood cut in twain or eradicated by a massive highway. The Greenwood community’s Vernon Chapel AME Church is on the other side of the overpass as is the famous Mount Zion Baptist Church, which was rebuilt after the racial terrorists destroyed it. The scrappy and informative Greenwood Cultural Center is across from the Vernon Chapel on the edge of the Tulsa campus of Oklahoma State University. Just behind the western stance of Greenwood storefronts is a beautiful minor league baseball field, home of the Tulsa Drillers, an LA Dodgers’ Double-A affiliate.

Yup. Right there. A handsome ballpark plopped on top of the site where people resided, businesses prospered, and lives were disappeared. Sacred ground. Massive photos of ball players and spectators decorate the front entrance. Every single person depicted in those photos when we visited was white. The stadium backs onto Greenwood, where its large rear gateway abuts the surviving Greenwood buildings with no apparent recognition of its historical or cultural context whatsoever. Imagine if someone proposed building a ballpark where the World Trade Center used to stand. Well, Tulsa built that ballpark.

Around the ballpark, on Greenwood, and in the area, small plaques — and a lot of them — are embedded in the sidewalk with the names of business and their proprietors that were located on those spots in 1921 — two dimensional remembrances of bustling business. I believe these were installed by the Greenwood Cultural Center, but don’t quote me.

If you look hard enough, you might find a meandering pathway just north of the stadium that features displays dedicated to racial and Tulsa history. Geoff and I only stumbled upon the pathway because we were looking for a shortcut in the heat. Now, at least, you know to search for it. The walkway sort of connects Greenwood Avenue with the beautiful and dignified John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park to the northwest, a place of solemn contemplation.

Did I mention the Greenwood Rising museum? No. That’s because it was closed. One year after opening, the state-of-the-art, beautiful (from the outside) Greenwood Rising museum was shuttered without so much as a sign to explain why. As Geoff and I stood outside in 100+ degree heat trying to grasp the situation, a large passenger van pulled up full of tourists who looked just as baffled and disappointed as we were. They evaporated into the bright sun. The museum website says it was closed for the month of August — you know, tourist season. As with so much in Tulsa, even this new museum, we later learned, is racially fraught, a feint toward “reparations” that came about with limited community input and which remains a source of righteous indignation. It, like the Bob Dylan Center, the Woody Guthrie Center, and many other fine public sites in Tulsa, was heavily funded by the George Kaiser Family Foundation. The simple fact is that, instead of sponsoring a renovation of the existing Cultural Center as intended, the commission with all the money went and built its own museum without fully dealing in the community.

Of course Geoff and I could discern none of this at the time. All we knew was that we were disappointed and uncomfortably hot. After being rebuffed by the handsome sealed doors of Greenwood Rising, we tried to self-tour the area. A sophisticated app from Greenwood Rising was supposed to help but is useless if there is any sunlight as there tends to be during the daytime. We wandered along roasting pavement, finding out what we could before making our way under the highway and to the Cultural Center.

Envision this spectacle, two overheated middle-aged white men hauling their ungainly balding selves up and down empty sidewalks trying to make sense of what we were seeing and, more to the point, not seeing. There were few markers aside from the ones embedded in the sidewalks. You could buy Black Wall Street souvenirs or take a picture of the famous mural painted on a wall under the highway, but Black Wall Street itself was gone. Mission accomplished. We let the terrorists win!

Later that evening, we met up with activist Kristi Williams in a coffee shop. Geoff had gotten her contact information from a mutual friend, and here we were in the back of this shop with a small group of Black women who were there to discuss the campaign of Tulsa’s only African-American City Councilperson, Vanessa Hall-Harper. Vanessa and Kristi were very welcoming to these two awkward, out-of-town tourists. We did not want to be interlopers during their meeting and made arrangements for the following day to meet Kristi although we could have stayed. Maybe the dissonance we were beginning to feel could have been channeled more productively if we had.

That next morning, Geoff and I went to the Bob Dylan Center, which as I said, was fabulous. Then we headed a few blocks to Greenwood to have lunch at Wanda J’s where some other tourists whom we had seen wandering the BDC were dining. Greenwood is a lunchtime destination for BDC visitors.

Afterward, we met Kristi at the Cultural Center, which was bustling in contrast to the day before. Kristi brought us into a busy office suite to introduce us to Dr. Tiffany Crutcher. Tiffany is the founder and director of the Terence Crutcher Foundation, which seeks to foster structural and progressive change in the region. She named the foundation in honor of her twin brother who was gunned down by the police on a Tulsa street in September of 2016. You can see video of this — “tragedy” is another inadequate word — catastrophe in the documentary Who We Are. I, for one, am always torn apart by these videos of extrajudicial violence and executions. The horror of these snuff films themselves torments, but I am pulled in two directions. Do I bear witness, or do I look away out of respect? I must admit, I often find myself squinting as I watch them as if in compromise between dueling imperatives — similar to the increasing incongruity we were feeling on our visit to Tulsa.

Tiffany’s foundation is quite an accomplishment as it fulfills two roles: bringing awareness to what has been and what is while seeking justice for the same — education and activism. In our brief conversation with Tiffany, she helped us understand a little more just how fraught Tulsa is. Tiffany and Kristi brought us to more of an awareness than we otherwise would have been able to access. Their twin missions are to fill in that which has been and continues to be erased. Time is not on their side. They too are collectors, seeking to help us recollect the past and understand the present in order to construct the future.

Afterward, Kristi took us back down the single extant Greenwood block to view the lone building facade that serves as a memorial of sorts. The facade has been clad in bricks that had burned in a nearby brickyard during the firebombing. These scorched and sometimes even melted bricks quietly testify to the unyielding violence of the inferno that had been Black Wall Street. Aside from the buildings themselves, which had all been refurbished, this was the only remaining tangible evidence of the massacre that we saw on that site. It required someone to point it out and explain it, though.

Kristi then directed us to the only other physical remnants of the 35 vibrant blocks that comprised Black Wall Street. Northwest of the Cultural Center, past the lovely labyrinth and powerful monuments of the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, on a quiet, out-of-the-way road, there is a long row of cement steps embedded in a small hill. They are evidently the front stoops of a block of houses along with some fragments of foundation walls — what is left of homes that once were the fluid life centers of the Black families who filled them.

These are the “Steps of No Return” or “Steps to Nowhere.” I’d say they are famous or infamous, but they are all-but anonymous, nondescript remnants in a forgettable location. The obvious assumption is that the 1921 racist terrorists had eradicated the houses and, more poignantly, the families whose lives had flourished in them. According to that telling, the cancel culture that is white supremacy then went to work to cancel the memory of the massacre and of Black Wall Street and of the thousands gone, and damn-near succeeded. More tellingly, though, the steps were probably not the result of the 1921 spasm of white supremacy but of the less singular and much later white supremacist blight of urban renewal. Geoff and I wandered among the steps in the bright sunlight, trying to imagine what must have been — the dynamic neighborhood that was absent. It is impossible for me to even picture such life in a place so devoid of it.

These Steps of No Return are as powerful a monument to Black eradication as we encountered. I thought of how after 9/11, pieces of the World Trade Center were sent to various locations all over the world. When I lived in Baltimore, many times I walked past a giant chunk of melted steel that had been installed as a monument at the Inner Harbor, but even that powerful artifact could not move me nearly as much as these steps. After all, the twisted beam was merely an internal and formerly hidden element of the superstructure. These steps, though, are a superior symbol. Of all architectural features, what is more human than steps — literally designed and built to accommodate the uniquely upright human frame, structures we climb with such ease that most of us rarely even notice them? And what evokes a home and the family that dwells in it more than its welcoming entrance? People sat here, laughing, arguing, visiting with friends. Lovers smooched here, and soldiers departed to fight in the Great War, some never to return, others to return and fight again in spring of 1921. At holidays, family members mounted these steps to give and receive greetings, hugging and kissing at the top in the doorway. Kids stumbled down these steps, skinned their knees, and kept going. These steps were at the forefront, literally, of the lives of the families that lived in these absent homes. Yet, these entrances to nowhere bore witness to mass murder and destruction and evoked horror in ways that a giant melted tangle of steel mounted on a pedestal or even burned bricks displayed on a storefront facade could not.

If you watch Who We Are, you will see Kristi Williams as she leads the filmmakers on a visit to these Steps of No Return.

Thus is the fraught racial reality in Tulsa. Tiffany Crutcher and Kristi Williams both appear in a documentary about racism in America but for entirely different reasons, Tiffany on behalf of her murdered brother and her foundation and Kristi on behalf of the dead and displaced of the Tulsa Race Massacre. But, then again, are they really different reasons at all?

Our National Idiot Wind

Later in our trip, when Geoff and I visited Mississippi, we could see another type of racial erasure. Sure, folks have gone to great lengths to mark the spots where Muddy Waters lived or where such-and-such juke joint stood, but in many cases, as with the steps, no edifice of stature remained.

In the case of Clarksdale, the erasure was probably more the result of time and disregard than of concerted effort since the sites themselves originated in the tenuousness that scarcity engenders. Of course, that reality only proves that oppression and unconscious neglect lead to an oblique violence just as terminal as the acute violence of a police gun fired point-blank at a distressed Black man in a Tulsa road. Both the oblique and the acute leave the same remains — empty landscapes, absent loved ones, and, eventually, something erected new in their place. In Mississippi, despite a latter-day recognition of genius and music, there is little acknowledgement of the conditions under which those great blues artists lived — some for their entire lives. The Blues Trail Markers of the Mississippi Delta are not unlike London’s famous Blue Plaques in that they are nice to visit but little else.

In the early twentieth century, Tulsa and the Delta were loci of racial animus, oppression, and suffering. But then again, so has been virtually every area of the American landscape. Our very history, our collective memory, is marked by absence and erasure. For instance, I grew up near Philadelphia and was taught that people were not enslaved in the North, which is a patent falsehood. Who We Are does a good job of sketching the reality of the Northern slave trade and bringing out how, even after banning slavery from their territory, Northern states benefitted financially from Southern brutality. Frankly, I learned something new from the film. Did you know that the mayor of New York City wanted his town to secede from the Union along with the Confederacy because America’s financial capital relied on the labor and productivity of the South’s enslaved people?

Getting back to the blues, standing there in Clarksdale, my head spun with dissonance again as I at once wondered at the miracle that is the blues and contemplated how we still benefit from slavery and its heirs: sharecropping, Jim Crow, lynching, poverty, and the prison-industrial complex to name a few. Without these conditions and the concentration of such things in the Mississippi Delta along with African musical traditions and gospel music born of field hollers, we would never have heard one note of the blues and its heirs: jazz, R&B, rock, and country, to name a few.

The murder of Terence Crutcher, the struggle of sharecroppers, and the Tulsa Race Massacre are parts of a larger traumatic, nation-enveloping whole. An erasure driven by racism, our national “Idiot wind”:

Blowin’ like a circle around my skull From the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol.

The Fraught Location of the Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie Centers: “This Land Is Your Land”

The Bob Dylan Center is one neighborhood over from Greenwood in the recently rebranded Tulsa Arts District, formerly known as the Brady Arts District. Brady, you may recall, is the name on that theater I mentioned earlier in which so many terrified Black men were interred, some reportedly never to emerge. It also had been the name of the street that the BDC stands on, which has been rechristened “Reconciliation Way.” The way to reconciliation, if you haven’t caught it, is through a predominantly tony white section of Tulsa, full of museums and restaurants.

Brady is W. Tate Brady, a favorite son of Tulsa for a certain set. Tate Brady was a founder of Tulsa and prominent businessman. As you may have guessed, Tate Brady was a virulent racist. Although he married into the Cherokee tribe, he was instrumental in fostering the Klan in Tulsa and was involved — being a favorite son — in the 1921 massacre. Afterward, he helped try to displace the Black population even further as part of some sort of fucked up proto-redlining real estate scheme, a scheme that was fully realized in the building of Interstate 244, which you already met. His is a bitter and appalling legacy, one that until very recently was widely honored in the Arts District and throughout Tulsa. Lately, after much resistance, city leaders have begun to strip his name from various city sites. The pain, though, lingers, and you can still easily find vestiges of his name.

My guess is that few who visit the BDC have any idea just how fraught and raw this legacy is. Kristi Williams — true to her commitment “to no longer be a victim of symbolic gestures of the killing, the oppression and just the horrible treatment of [her] ancestors” — will not set foot in the Arts District and, by extension, the BDC. She likes to point out that Bob Dylan reportedly has also never visited the Center. Given that Dylan eschewed his own Nobel Prize ceremony, I am not sure his absence, though, tells us anything about his views on its location.

What visitors must recognize, what the BDC curators are apparently sensitive to, and what I have only begun to grasp after interacting with Kristi and her associates, is how racially fraught Tulsa is even by American standards. The Arts District is fraught. Anything associated with the Arts District is fraught. The Kaiser Family Foundation is fraught. On and on. And, let’s face it, the BDC is a gilded bastion catering to whiteness in the midst of a white district nestled next to the former Black Wall Street, one of the most historically and presently racially fraught areas of the country. Or, it would be if the population had not been all but eradicated.

I am, of course, not saying that one should not visit the Bob Dylan Center. It is wonderfully wrought, and the staff is delightful. As well, visit the Woodie Guthrie Center for the same reasons. But, be aware of where you are. Tulsa, racially, is a messy place, and I say that having lived in Baltimore for many years, including the during the 2015 Uprising after the execution of Freddie Gray. In this, to paraphrase Dylan, Tulsa is not so unique, but please do have some sense of and sensitivity to the small bit that Geoff and I learned while visiting with Kristi, Tiffany, and Vanessa. Their great work is a vital attempt to document and educate and rectify. They are on a mission to save Tulsa and maybe even America by extension. Stop by the Greenwood Cultural Center. And why not catch the excellent Netflix documentary Who We Are?

In the spirit of Dylan, do not allow our inconvenient and unsightly wrinkles to simply be ironed out of the fabric of history. It behooves serious Dylan fans to acknowledge, collect, and preserve all our history and witness the present fraughtness of Tulsa, the evidence of what was that lingers. To do otherwise, as Orwell and the Tulsa activists teach us and Dylan apparently honors, is to risk forever damaging what is to be.

Here’s the video version if you prefer. I am wearing a Black Wall Street tee from the Terrence Crutcher Foundation that was given to me by Tiffany Crutcher.

If you like what you hear, please share.

The Dylantantes is a proud member of the FM Podcast Network. Listen to it wherever your find your favorite podcasts and subscribe for full access to all the network programs.

Share this post